How Judges Get Governing Wrong

When they haven't governed, they can misunderstand that work

In this column:

Judges can inhibit good governing

Today’s judges lack governing experience

Originalism won’t solve this problem

Those interested in American public life need to appreciate how bad judging stands in the way of good governing.

For those who don’t read this column regularly, by “governing” I mean executing the authorities and carrying out the responsibilities of executive-branch and legislative-branch offices. This includes passing laws, holding hearings, appropriating funds, pursuing investigations, running departments, monitoring grants, publishing rules and guidance documents, issuing executive orders, administering programs, and the like.

There are a number of ways that judges inappropriately hinder those doing this work; and we should never forget that those doing this work are constitutional and statutory officers in their own right. For instance, judges might get separation-of-powers issues wrong, thereby inflating the power of one branch at the expense of another. Judges might give officials too much authority or too much leeway. The biggest type of mistake, however, is the invention or improper expansion of rights: Rights almost always limit governing, meaning when a court concocts a liberty (without sufficient statutory or constitutional language), that court stops governing officials from doing important parts of their jobs.

Judges of All Ideologies Can Get This Wrong

Before going any farther, I should make one thing clear: Both right-leaning and left-leaning judges can get governing wrong. So my argument here operates on a different axis that the progressive-conservative dimension that most Court observers discuss. Now, yes, it is absolutely true that progressive justices have more often mis-adventured with rights (i.e., infamously, the imaginative judicial-activism, living-constitutionalism rulings of the Warren-Burger era). But right-leaning actors have gotten governing things wrong, too: Some conservative justices supported the misguided Chevron doctrine which expanded administrative power; some libertarian scholars have supported the misguided, rights-centric “judicial engagement” school of thought; conservative justices have sometimes been too rights-focused on pandemic-era rules and gun regulations, Justice Gorsuch’s Bostock decision typifies a “living textualism” that undermines legislative decision-making. (But the conservative justices deserve credit for getting governing correct in Dobbs, non-delegation cases, and the Major Questions Doctrine.)

In my next column, I’ll focus on a few specific examples, primarily the terribly misguided SCOTUS decision in the “cursing cheerleader” case. But I’ll also discuss distorted textualism, guns rulings, Trump vs. United States, and the risk of the post-Chevron era (as well as Myers v. United States which the Court got right).

But here I want to focus on one of the key themes of this column: The need for more people who care about public life to actually get involved in governing.

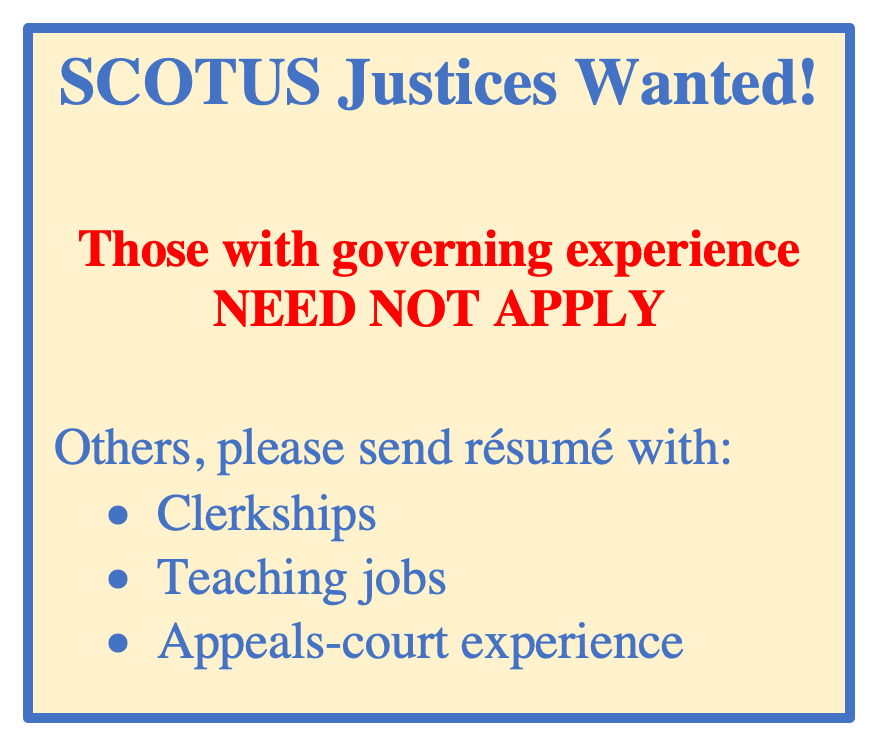

In this context, that means pointing out that we are in a very unusual, very unhealthy era when our nation’s top judges have virtually no meaningful governing experience. Though this applies to federal appeals court judges, I’m going to talk about SCOTUS where the problem is most pronounced.

Judges Used to Have Governing Experience

For most of American history, it was common to find lots of governing experience on the US Supreme Court. Chief Justice William Howard Taft had been President of the United States. Several other chief justices, including John Rutledge and Charles Evans Hughes, had been governors. Seventeen justices served in the US House (including John Marshall and Joseph Story); 15 served in the US Senate (including Hugo Black and Salmon Chase). In total, if we include the host of state and local offices, 58 justices had elected governing experience. This doesn’t include the many others who’ve had state and federal governing experience in appointed offices. These types of background experiences matter.1

When you serve in these capacities, you take an oath of office to do a job. You have explicit and implicit duties. You are shaped by the office you hold and the people you represent and serve. You will have, I am convinced, a greater respect for the needs and responsibilities of similar officials. You will certainly better understand what those officials face. You will also understand how judges can get in the way of the essential work of these offices.

Unfortunately, for several generations now, especially today, the path to SCOTUS does not lead through governing. It seems to avoid positions of governing like they are potholes, ditches, or, perhaps better said, scenic distractions. Instead, the path goes from elite college to elite law school; to clerking for several judges; to maybe some private practice and/or a bit of teaching; to some work at the Department of Justice and/or White House; then a federal appeals judgeship before the high court.2 If you’ve not done so recently, you should look at the astonishingly similar bios of today’s Court.

In an excellent article on these issues, “An Empirical Study of Supreme Court Justice Pre-Appointment Experience,” University of Tennessee law professor Benjamin Barton found that members of the John Roberts Court (since 2005) “spent more pre-appointment time in legal academia, appellate judging, and living in Washington, D.C. than any previous Supreme Court.” As Barton wrote, “These cloistered and neutral experiences offer limited opportunities for the development of the most critical judicial virtue: practical wisdom.”

The study found that all justices combined (from the Court’s founding) had 500 years of elective-office experience. But no justice in the Roberts era has even a single year of such experience. In about 1850, the average justice had nine years of experience in elective office; those days are a distant memory. “The retirement of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor [2006] ended a continuous tradition of at least one former politician on every Supreme Court from Jay 1 forward.” Moreover, in the nation’s first 50 years, justices generally had a good bit of “non-law government experience,” essentially non-elected government positions that aren’t focused on legal practice (roles that fit nicely in my understanding of “governing”). At the peak, the average justices had almost eight years of such experience; in the Roberts era, it’s about a year and a half.

In another excellent law-journal article, “The Case for Returning Politicians to the Supreme Court,” Robert F. Alleman and Jason Mazzone write, “As the Supreme Court has become filled with former judges, it has lost one kind of Justice who was very nearly a constant on the Court for 170 years: the politician who joins the Court after distinguished and prominent service in public life.” Among the reasons they cite for more individuals with such governing experience: “They also bring wisdom and skills that vastly improve the work of the Court.”

Indeed. The wisdom and skills that come from governing would help the Court significantly.

Originalism Won’t Solve This

One final provocation.

I suspect that originalism and textualism—the dominant philosophies of interpretation on today’s right—play out different when used by those with significant governing experience and those without. In other words, judges who know little about being a state legislator, governor, or cabinet secretary will, I imagine, interpret statutory and constitutional language and principles differently than those who’ve served in those types of capacities.

My suspicion is that those who wrote the Constitution—given that they had an enormous amount of governing experience in the Colonial and Republic eras—would have understood the Constitution as giving a great deal of deference to those in governing roles. Although they were committed to liberty, the framers, I bet, would have understood better than today’s judges that a rights-first posture would prevent executive and legislative branch officials from carrying out their duties.

To be clear, I’m still a complete believer in originalism and textualism. They must be the baseline for interpretation. They are fair, reliable, and transparent, and they reflect and respect our republican tradition of self-government. However, they must be leavened by additional approaches that enable governing officials to govern. This is doubly true for as long as we’re in an era where judges lack governing experience. For instance, I’m partial to James Bradley Thayer's approach of deferring to legislatures and and John Hart Ely’s approach of prioritizing democratic decision-making.

In my next column, I’ll provide some more specifics. But for now, I’ll end by repeating myself:

It’s a problem for American republicanism that so few judges have governing experience.

See footnotes 19, 20, 21, and 22 of this study for citations showing that experience as an academic, prosecutor, judge, and politician influences SCOTUS decisions.

Though jobs at DOJ and the White House counsel’s office are executive-branch positions, they are practice-of-law jobs.