The Constitution's Neglected Clause

Reanimating the "republican form of government" provision in the Maine legislator case and beyond.

Many Court observers have a constitutional provision they believe to be neglected. For years, conservatives argued SCOTUS ignored the 10th Amendment to the detriment of states. Some liberals have thought the 9th Amendment should be invoked more often to protect individual freedom. Currently, some argue for the reanimation of the “Privileges or Immunities Clause.”

In actuality, the most neglected provision of the U.S. Constitution is the “Guarantee Clause,” better known as the “Republicanism Clause.”

Had the Court explicated and applied this provision generations ago, it would have been front and center in the current case of the silenced Maine legislator (Libby v. Fecteau). But it also could have (i.e., should have) played a role in cases related to presidential immunity, the pardon power, the Commerce Clause, the incorporation doctrine, federalism, the Supremacy Clause, the administrative state, the independent state legislature theory, and more.

By ignoring the Republicanism Clause, we’ve chipped away at self-government and state authority while allowing Washington’s power, federal rights, and executive-branch agencies to expand.

Republicanism Yesterday and Today

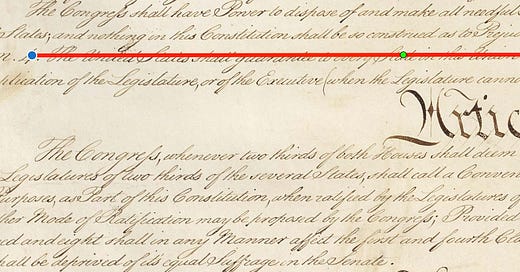

In Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution, states are guaranteed a republican form of government. On its face, the provision helps explain why state governments have governors, legislatures, and courts—that is, why states aren’t military dictatorships, don’t have politburos, etc.

But what exactly does the “republican form”—and more broadly, what does “republicanism”—require? This would seem to be an obvious question. Given the historical meaning and importance of republicanism, it’s remarkable how silent SCOTUS has been on the subject.

Republicanism was foundational to the framers. They studied the theory and practice of republics going back centuries years. They were clear about some of its essential features. They explained how America’s implementation of republicanism would differ from previous versions. I describe much of this in a long essay I wrote for National Affairs a few years ago called “Recovering the Republican Sensibility.” In short, the framers understood republicanism to require sovereignty, democracy, duties of citizenship, limits on the state, civic virtue, equality, and state power related to the common good.

Critical for the interpretation of the Constitution, the concept of republicanism was central in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist Papers. “Republic” or “republicanism” appears in the Federalist Papers more than 160 times. Several of the key debates between Federalists and Anti-Federalists were about what republicanism required. The concept was front of mind in the drafting and ratification of the Constitution.

Over the ages, the Court has crafted and applied principles and doctrines not explicitly in the Constitution: substantive due process, the dormant commerce clause, qualified immunity, the penumbras and emanations adumbrating a right to privacy. It is notable that something explicit like republicanism has been largely shelved.

In the handful of cases that have addressed the clause head-on (a thin slice of the cases that should have addressed the clause), the Court has mostly chosen not to engage with the concept of republicanism or focused narrowly on voting-related matters (see here, here, and here; though In re Duncan and Cruikshank very briefly engage more broadly). For instance, the Court made a grave mistake in Pacific States Tel. & Tel. Co. v. Oregon (1912) in declining to give meaning to the provision and saying it was a political matter reserved for Congress. The Court had taken up the provision in Luther v. Borden (1849) to say that when two state entities claim to be the legitimate republican government, Congress decides. But that opinion began the Court’s position that defining and enforcing the clause was a political (non-justiciable) matter. Similar cases followed suit with a summative statement coming in Rucho v. Common Cause: “This Court has several times concluded that the Guarantee Clause does not provide the basis for a justiciable claim.”

My view, however, is that a matter should be understood as non-justiciable if it is clearly in the remit of another branch and/or should be left to other entities or individuals for political or practical reasons. Since this provision implicates the nature of state-level governing, we need the Court to say (as the Court likes to remind us only it can do) what the law is. If anti-republican rules allow one branch of state government to dominate the others, perpetually deferring to the political process would only lock in the problem. In other words, courts must ensure the republican nature of the system so that the political process can work. And because the federal government is not a disinterested party to the question of state-level power, we can’t leave “republicanism” up to Congress alone to decide.

Republicanism in Action

One possible downside of greater Court engagement is that a more muscular republicanism clause could enable mischief. A progressive Court could invoke the guarantee of a republican government to manufacture new rights and/or force states to do things that progressives want. That is, justices could read their political preferences into republicanism. (See this 1994 article by Professor Erwin Chemerinsky: I somewhat agree with its take on justiciability and political questions, but not on how the clause would be used.)

But I think the faithful application of republicanism’s principles would serve as a powerful check against rights-creating courts, an ever-expanding federal government, and a powerful administrative state. More than a century ago, the Court should have explained that American republicanism is about the right of the people to self-govern. That implies both democracy and state-level sovereignty. It means the people have the power, unless explicitly constrained, to rule themselves according to their sense of the common good. Given federalism, this means the right of states to govern themselves differently via policy (within the bounds of republicanism’s institutional arrangements). It also means—because of the centuries-old understanding of civic or republican virtue—that citizens have duties and that governing officials are limited in their powers and can be punished for misusing public authority.

Had the Court done this, and had subsequent decisions filled out the requirements of republicanism, we (the people, the judiciary, etc.) would view many legal issues today differently. Here is a possible list of examples:

The current case of the Maine legislator who had her voting rights revoked because she posted something untoward on social media. Many observers see this as a free-speech case, but it is clearly a matter of the republican form of government (even though the legislator’s application for injunctive relief mentions republican governing but once in passing). Under republicanism, a duly-elected representative of the people shouldn’t be disenfranchised in this way.

States would have had additional grounds to resist the federal judiciary’s creation of new rights throughout the 20th century. The recognition of state-level republicanism should limit intrusions into state-level self-governing. SCOTUS should have had to wrestle publicly, explicitly with the question of when the overturning of state laws by federal courts begins to impinge on states’ republican form of government.

States, invoking the republican form and the 10th Amendment, would have had a stronger hand when resisting federal activity in areas reserved for state governments. (The Court touched upon this possibility in Gregory v. Ashcroft [1991]).

States might have had stronger grounds to shape the incorporation doctrine. The guarantee of republican governing could have been invoked to elevate the states’ role in defining liberties.

States and citizens would have had stronger ground to object to the undemocratic nature of some agency actions at the state and federal level. Our courts would have had to engage in a serious discussion of when executive-branch rules and enforcement intrude on republicanism.

Various forms of immunity for public officials, including that established in Trump vs. US, might have been constrained. Republicanism is hostile to abuses of official authority.

The judiciary might have been sympathetic to arguments in favor of constraining the executive pardon power. The pardon power would not be seen as absolute. For instance, self-pardons would be viewed as inherently impermissible, and pardons of family members and pardons issued in conjunction with potentially criminal activity could be prohibited by law.

The clause would be front and center in cases like Moore v. Harper, where the powers of different branches of state governments are in tension. (In this decision, SCOTUS did not even mention the clause.)

History, Tradition, Text, and Republicanism

Yes, this list of counterfactuals is provocative. But my purpose is to demonstrate that this provision should have—or at minimum could have—been given far more weight. That would have increased the legal standing of republicanism’s demands, and, more concretely, it would have given state governments a stronger hand in checking a variety of federal actions.

We’re in an era when, thankfully, courts are giving more attention to history, tradition, and text. All three of those counsel reanimating the Republican Form of Government Clause.

Does this line of thinking have any relevance to state preemption over local government authority?