David Souter (R.I.P.) as Turning Point

His confirmation energized the right. But elite, New-England progressivism energized populism.

In this column:

A good man and committed public servant

Conservatives’ long list of judicial disappointments

How judicial elitism spurs populism

Justice David Souter’s elevation to the U.S. Supreme Court 35 years ago was a turning point. It was the last straw for conservatives furious and embarrassed by decades of routs at the high court. But it could also—and this might be wishful thinking on my part—come to be understood as the beginning of the decline of progressive, New-England, managerial jurisprudence.

Honorable Service

First, there is much to admire about David Souter, who passed away last week at the age of 85. He was a decent and intelligent man. Two degrees from Harvard and one from Oxford thanks to a prestigious Rhodes Scholarship. He was a committed public servant: Prior to his SCOTUS nomination in 1990 by President George HW Bush, he was a state attorney general, a state supreme court justice, and a federal appeals court judge. He was temperamentally restrained, never seeking the limelight, seldom writing angry, preferring to go about his work quietly. When the Court’s term ended each year, he decamped to a secluded New Hampshire farmhouse to read old books. He didn’t give high-profile lectures or go on self-aggrandizing book tours. He had an ascetic lifestyle, loved his monastic job, and disliked Washington, DC.

I applaud David Souter’s character and service.

Just not his jurisprudence.

The Post-Souter Right

After his confirmation, Souter swiftly made himself comfortable on the Court’s left. For 19 years, he was consistently among the most liberal/progressive justices. He had few memorable, much less era-defining, opinions; he is generally considered a fine, not a great, justice (though his concurrence in Glucksberg is worth reading). He was a reliable vote for the left in virtually all of the notable cases of his time: He was a predictable “no” vote as conservatives on the Court mobilized to tame the administrative state, strengthen federalism, protect religious expression, etc.

Historically, however, Souter is important for being one in a long line of GOP-appointed justices who ended up as progressives, such as Warren, Blackmun, Brennan, and Stevens. After Souter, the right finally internalized that it was partially to blame for the Court’s liberal decisions. Indeed, had Souter and two other Republican nominees (O’Connor and Kennedy) not contrived the difficult-to-defend Casey decision, Roe would’ve been a 20-year, not a 50-year, mistake.

From that point on, conservatives were determined to ensure that GOP nominees to the Court were actually conservative. When President George W. Bush nominated Harriet Miers in 2005, the right said, “No.” There was simply no evidence that she would be a conservative judge. No more blind trust, the right said. No risking another Blackmun, Brennan, Stevens, or Souter. Her nomination was scuttled, and she was replaced by Samuel Alito, who, in a remarkably literary turn, later wrote the Dobbs decision overturning Casey and Roe. The right was vindicated.

It is not too much to say that the Federalist Society’s huge role in proposing and vetting judicial candidates over the last 30 years is partly attributable to Justice Souter. It is not too much to say that the right fought so hard for Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett partly because of Justice Souter.

Politically speaking, the modern era of conservative engagement with the judiciary can be split into two periods: before Souter and after Souter.

Progressive Managerial Jurisprudence

There is something undeniably hubristic about the progressive approach to constitutional law. Judges presuming to “update” the Constitution based on their personal views about progress. Judges manufacturing rights at the expense of democratic decision-making. Judges siding with “expert” administrators over the people’s representatives. Judges putting their predictions and perceptions of consequences above statutory or constitutional text.

We should recognize this as “progressive managerial” jurisprudence. Just as progressive technocrats believe their smarts and virtue enable and entitle them to manage other people’s schools or big parts of the economy, progressive-managerial judges feel entitled to manage the law to their desired outcomes.

I believe that more than a little anti-democratic elitism energizes progressive-managerial jurisprudence. And as I recently wrote, I’m concerned that this is a significant factor in our current “era of perpetual populism.” Part of my argument is that we have too many leaders who hail from and work in a mostly progressive sliver of America. They are surrounded by people like themselves, and they know too little and care too little about the sensibilities of the rest of America. As a result, they can give the strong impression that they look down on much of the nation and that they are willing to replace others’ preferences with their own.

It is hard not to notice how many progressive justices were schooled in and/or built careers in and around these elite New-England circles and institutions. Using a widely cited source for justices’ ideology, we can see how pronounced this phenomenon is: Professors/deans of Ivy law schools (Kagan, Douglas, Fortas, Breyer), judges on the New England-based 1st Circuit (Breyer) judges on the New England/NY-based 2nd Circuit (Marshall, Breyer, Sotomayor), two or more Ivy degree (Blackmun, Brennan, Kagan, Ginsburg, Jackson, Sotomayor…).

And, of course, Souter was part of this phenomenon: Twice a Harvard graduate, a New-England state judge, a First Circuit judge, etc.

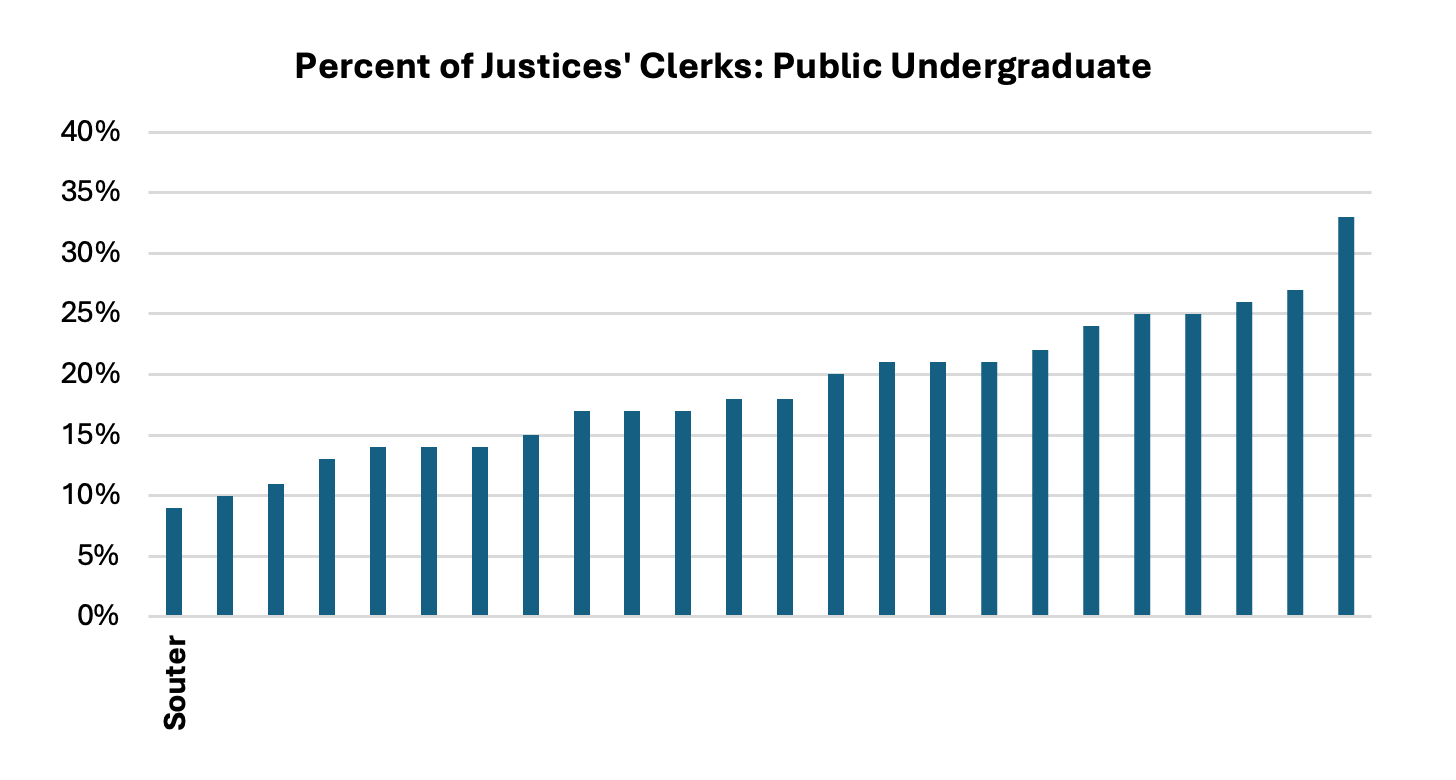

Moreover, in my recent research on US Supreme Court clerks, I found something else. It speaks directly to my concerns about elitism and populism. In the last 45 years, no justice was more elitist in the hiring of clerks than Souter. My report (coming out before too long) will provide much more detail, but for the time being look at the following graphs. (I’ve erased the other justices’ names so as to not steal the full report’s thunder.)

Since 1980, no justice hired a smaller percentage of clerks from public colleges than Souter. No justice hired a higher percentage of clerks from Ivy colleges than Souter

At the law-school level, only two justices chose fewer public grads than Souter (and both of those justices were also New England-shaped progressives). And only one justice chose more Ivy law grads.

The US Supreme Court—and our entire leadership class—needs more humility and a greater republican sensibility. We need more leaders who appreciate that talent is found across America and in all sorts of schools; we need leaders who understand and appreciate that not all wisdom and virtue is found from New York to Maine; we need leaders who will allow the constellation of states and municipalities to govern themselves; we need leaders who understand that elite, cosmopolitan values are not the only legitimate values.

As seats on the Court open up, I hope our presidents look for folks with democratic-governing, not just judicial, experience. If they desperately want to pick federal appeals court judges, I hope they avoid the First and Second Circuits. I hope they look for public and regional-private grads, not just products of the Ivies. I hope they look for backgrounds that start not along the Acela corridor but in the South, Midwest, Great Plains, and Mountain West.

Populism builds when the people believe their leaders don’t know and don’t care about them. We need a Court membership that reflects and understands all of America, not just a corner of it.