Chesterton's Regulation

An imagined highway-fund scenario to explain why knowledge and prudence are needed when deregulating like DOGE

Maybe the biggest difference between a conservative and a progressive is that the conservative aims to preserve and move cautiously because there’s so much wisdom behind us while the progressive aims to bring about expansive change rapidly because there’s so much better ahead of us.

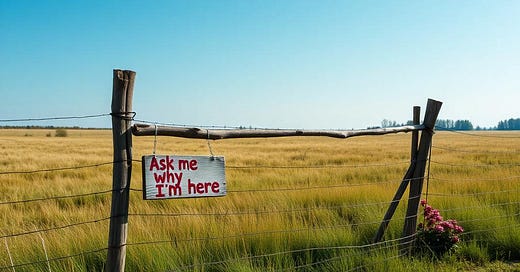

We conservatives often invoke “Chesterton’s Fence,” an adage that warns that you should always take time to understand why an old fence was put up (and why it’s stayed up for so long) before dismantling it. We think the left tends to show too little humility and tends to act too impetuously and too radically: They’d see an old fence, immediately declare it unnecessary or unjust, and then start taking it apart before appreciating why it’s there or the costs of bringing it down.

Radical Conservatism And DOGE

There is, however, always a strand of conservatism that thinks the left has changed so much so fast and done such damage to society that conservatives must temporarily put aside their impulse to preserve and move cautiously. They argue instead, interestingly, for a more progressive approach—rapid, expansive, unapologetic change—to return things to how they were.

I offer this conceptual introduction up front because I’m about to get seriously wonky about Elon Musk, DOGE, and light-speed deregulation. Bear with me, please.

Musk’s effort can be thought of as the radical kind of conservatism. It starts from the premise that the left has—to the nation’s detriment—vastly expanded the administrative state. Accordingly, DOGE aims to slash fast and deep so the federal bureaucracy can be returned (smaller, weaker) to how it ought to be.

I agree that the administrative state has grown too large and that its unelected officials have become too powerful. I think that trend is bad for policy, democracy, and pluralism.

The question, however, is whether slashing fast and deep—especially when the slashing is led by tech entrepreneurs with no governing experience, junior lawyers, and artificial intelligence—is the right approach.

To ask bluntly: Are we conservatives so excited about rapidly cutting federal rules that we’re on the verge of acting presumptuously, impetuously, and radically?

Do we need a conservative to invoke “Chesterton’s Regulation”?

Benign or Malign Regulation?

To show you what I mean, I’m going to create a) some very simple statutory language in an imaginary transportation law, b) several hypothetical consequences of the law’s indeterminacy, c) imaginary federal regulations crafted to address the confusions, and d) the upshot of a swift deregulatory process.

This is going to be fun. Well, as fun as regulation-talk can get when it’s about hypothetical closed highway exits, illegal bike paths, and protections for textile manufacturers.. But I hope you’ll see my broader point.

OK. Imagine that 25 years ago, a massive federal transportation law was passed, and it included a new program called that “Growth and Conservation Fund.”

The program authorized $500 million annually to help states and municipalities “build or upgrade highway and highway-related projects that will spur intra- and inter-state economic growth and help regional conservation efforts.”

Easy enough, huh?

Now imagine that in the program’s first year, California and Massachusetts decided to use these federal funds to demolish some highways and build bike and walking paths where the roads had been. The states defended the spending because these would be “highway-related” projects (a purpose of the law) and they would help economic growth since there would be yoga studios and coffee shops along the paths.

Since other states were liable to do the same, the U.S Department of Transportation issued regulations clarifying that the statute intended to 1) support highway projects, not bike paths and 2) spur economic growth comparable to or greater than the cost of the project, i.e., not a handful of lattes.

Now, imagine Indiana used its funds to close highway exits leading to Ohio and Kentucky. Those exits, Indiana argued, allowed ground transportation to bypass key Indiana businesses. Closing the exits would cause more trucks to stay in Indiana longer, which would spur Indiana’s “intra-state” economic growth, which is a purpose of the statute. In response, Kentucky and Ohio used funds to close highway exits to Indiana.

So DOT issued simple rules prohibiting funds to be used in ways that would purposely limit inter-state transportation.

Now, imagine a couple years later Alaska and Montana used their funds to build roads from small towns to vacant properties owned by wealthy, well connected residents. The states defended the projects because the value of the adjacent land would appreciate, hence meaningful “economic growth.”

So DOT issued new rules requiring each state’s department of transportation to attest that each project had a cost-benefit analysis conducted by a third party demonstrating the likelihood of “publicly beneficial” economic growth.

Now, imagine that a Democratic governor of Pennsylvania ordered the state’s share of funds be used to preserve historic cobblestone and brick streets in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. This, she said, was consistent with the statute’s prioritization of “conservation” efforts. But the state’s Republican Attorney General advised that the governor’s interpretation was inconsistent with the federal law. The “and” in the statute requires economic growth and conservation, not conservation alone. The state AG then prohibited the state’s transportation authority from spending the federal funds as the governor wanted. The issue was battled out in federal court for five years, during which time Pennsylvania was unable to spend any of the funds.

To end the lawsuit (and similar suits emerging in other states) the DOT issued rules clarifying how states should interpret “and” in this context as well as which types of road “conservation” projects were consistent with the law’s economic-growth goals.

Now, imagine South Carolina, committed to the “conservation” of the state’s textile industry, used the federal funds to close a highway to and from the Port of Charleston and build new roads from in-state manufacturers to in-state distribution centers. This use of funds, argued South Carolina, would protect local firms from imported Chinese textiles and therefore spur intra-state economic growth. Several states along the Gulf Coast then did something similar to protect local refineries from imported oil. Lawsuits from international-trade groups (which, understandably hated these state policies) led to different rulings—including conflicting injunctions—by several federal district courts.

Because the DOT was concerned that the Fourth and Fifth Circuit Courts of Appeals would reach different conclusions, which would only extend the legal wrangling, it issued new federal rules describing which types of projects aimed at industry “conservation” were consistent with the statute’s purpose.

That Fence Had a Purpose

Here’s my point. This is one imaginary program out of tens of thousands of federal programs. There is no way that a tech entrepreneur who knows nothing about governing could know anything about this program or its complicated history. AI wouldn’t be able to understand all of the twists and turns. Nor would a junior attorney tasked with investigating hundreds of other programs.

So at a morning meeting, one of those green attorneys reports to Mr. Musk, “Sir, with the help of AI, I identified an old transportation-funding program. Its statutory language is so simple. So straightforward. And yet these meddlesome bureaucrats at DOT crafted pages and pages of unnecessary regulations related to cost-benefit analysis, the meaning of “conservation,” the value of cobblestone streets, and the impact of yoga studios! It makes no sense!”

And Mr. Musk replies, “I’m going to contact the president! He must direct DOT to rescind all of these regulations immediately! Ha ha! Another victory for DOGE!”

To avoid a misinterpretation I almost fell into, notice that everything turns on Andy's second-to-last sentence--i.e., it is only the DOT regulations related to this law which DOGE can get Trump to eliminate. DOGE/Trump do not eliminate the poorly written law itself.

DOGE cannot go back in time and prevent all the shameful abuses of the law/program. Andy's point is that DOGE blindly eliminates all the DOT jerry-riggings of the law designed to prevent those abuses. Thus, many of them will happen all over again!