It’s the simplest question imaginable. And I had never considered it.

Do we have a duty to do the right thing?

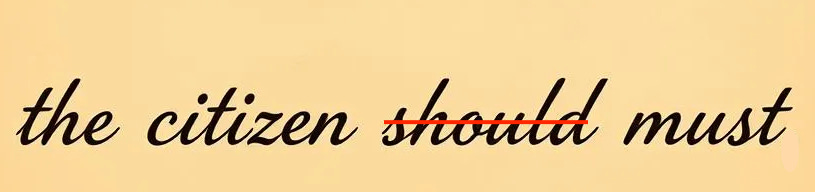

Daylight Between Right and Duty

Had I been asked this years ago, I’m sure I would have immediately replied, “Of course we do!” In fact, that answer would’ve been so obvious to me that I probably would’ve thought something was wrong with the person asking.

You see, I’m morally fastidious. OK, I’m borderline puritanical. On personality tests, I always spike on the “conscientiousness” dimension. I can’t stand dishonesty, hypocrisy, cruelty, lack of discipline…

So when the four philosophers on the “Partially Examined Life” podcast asked this question (while discussing Korsgaard), it suddenly dawned on me that there might be some daylight between acknowledging that something is morally right and having a duty to do it.

And this realization gave me a new way of understanding what I’ve thought of as the immorality or amorality of contemporary public life. And how to address it.

This conversation gets interesting once we put aside instances where there’s legitimate debate about what is “right.” So here I’m not talking about whether a tax rate should be 26% or 27%, or whether we need more guns or butter at any given moment.

Instead, I’m interested in cases where everyone involved—and most outside observers—would agree that something is right and/or something is wrong. These could be instances covered by the Ten Commandments, social rules of thumb, cross-cultural consensus, things you learned in Kindergarten, etc.

I also want to rule out cases where something is wrong but necessary to prevent something that’s even worse. Yes, lying is wrong, but if you must lie to save the life of an innocent person hiding from a mob, that lie is acceptable.

I’m talking about instances where we know something is right but really want to do something else that’s more convenient, that would make us feel good, that would hurt people we don’t like, etc.

So what are the forces that would compel us to do the right thing?

What Compels Right Action?

There are a bunch. One is law. If the right thing is required (or the wrong thing is prohibited), we might do the right thing to avoid punishment. Another is social norms. If we fail to do right, we could suffer public shame. Another is religion. We could believe that doing wrong will be sanctioned in the afterlife. Karma could lead us to believe that the universe will get back at us for doing wrong. Humans might also have an innate moral sense that leads them to do right.

But evidently all of this is insufficient. Lots of people in public life do immoral things. Officials take bribes and use public authority for self-gain. They lie. They practice nepotism. They act undemocratically, misleading the public about the president’s mental health. They are cruel.

I think one cause of this is the contemporary aversion to talking about virtue. The Ancients, America’s framers, and countless leaders in between believed that virtue was the foundation of sound leadership. But today it is virtually invisible in discussions of public life, and it is neglected in the education of future leaders.

Modern scholars of character discuss four categories of virtue. I’ll leave aside one of them (intellectual virtue). Moral virtue includes the traits associated with ethical behavior (honesty, integrity, justice, compassion). Civic virtue includes traits associated with being a good citizen, particularly in a democratic republic (things like civility, care for community, service). Performance virtues are instrumental for the other virtues (things like motivation, confidence, resilience).

In hindsight, I naively believed that moral virtue was obviously necessary and that it was obviously enough to compel people to do right. I was wrong. In this era in particular there are simply too many examples of people disregarding honesty, integrity, etc. for us to believe that a moral sense alone will adequately shape behavior. Even if people recognize that telling the truth is right and that behaving with integrity is right, they will not, in many cases, tell the truth, act with integrity, etc.

Though moral virtue is lacking across the political spectrum, Donald Trump’s unscrupulous behavior forced a public conversation about it. Arguably the most remarkable aspect of that discussion was the effort, in some quarters, to find morality in Trump’s actions. Several authors tried to make the case that he was virtuous. Importantly, however, those defenses are primarily built not on moral virtue (indeed, as one author wrote: “Trump ripped apart people he thought were weak. Sometimes he went overboard, but his supporters forgave his excesses because strength is in such short supply. Trump plays to win. And he knows that in war reaching across the aisle is usually a sucker’s game.”).

Instead, they primarily focus on performance virtues, like strength, toughness, courage, resilience. This is key because performance virtues are meant to be instrumental. They are not good in and of themselves. They are good when they enable goodness. But, of course, we can be strong in our immorality. We can be tough in our immorality. We can be courageous and resilient in our immorality. Indeed, lies and cruelty from the political left have also been executed with strength and determination.

In other words, performance virtue won’t solve the problem I’m most interested in here: How do we close the gap between knowing what is right and doing what is right?

We don’t need more people doing wrong with courage and conviction.

Civic Virtue as Instrumental

Civic virtues should certainly be seen as ends. We should be civil, neighborly, and service-minded because that is proper.

But perhaps civic virtues should also be seen as instrumental—the way to ensure those involved in the public’s business feel compelled to do the right thing. Said another way, if morality, faith, social norms, and karma aren’t enough, maybe one’s commitment to the community’s common good will be.

Civic virtue has, for more than 2,000 years, been understand as the set of duties possessed by individuals who live in a community—the things we must do, the things we owe to others, so we can all live in peace and flourish.

While some of those who behave immorally in public life do so out of selfishness or worse, many do so because of a distorted sense of civic responsibility. They convince themselves that they are serving the public interest and behaving badly is just an occasional necessary consequence of that. In truth, it is seldom, seldom the case that immorality is in the public interest. But if their sincere aim is to advance the common good, they need to be reminded that being a good citizen and good public servant cannot be separated from the duty to do right.

It is antithetical to the common good of a democratic republic to lie to the people, to poison the public square, to demean opponents, to threaten, to partake in political violence. We are unable to act as a self-governing community when those in public life feel no duty to do the right thing.

If you care about civic virtue and the common good, you must recognize that there is virtually no daylight between recognizing what is right and an obligation to do what is right.

Serving America through public life requires moral virtue.